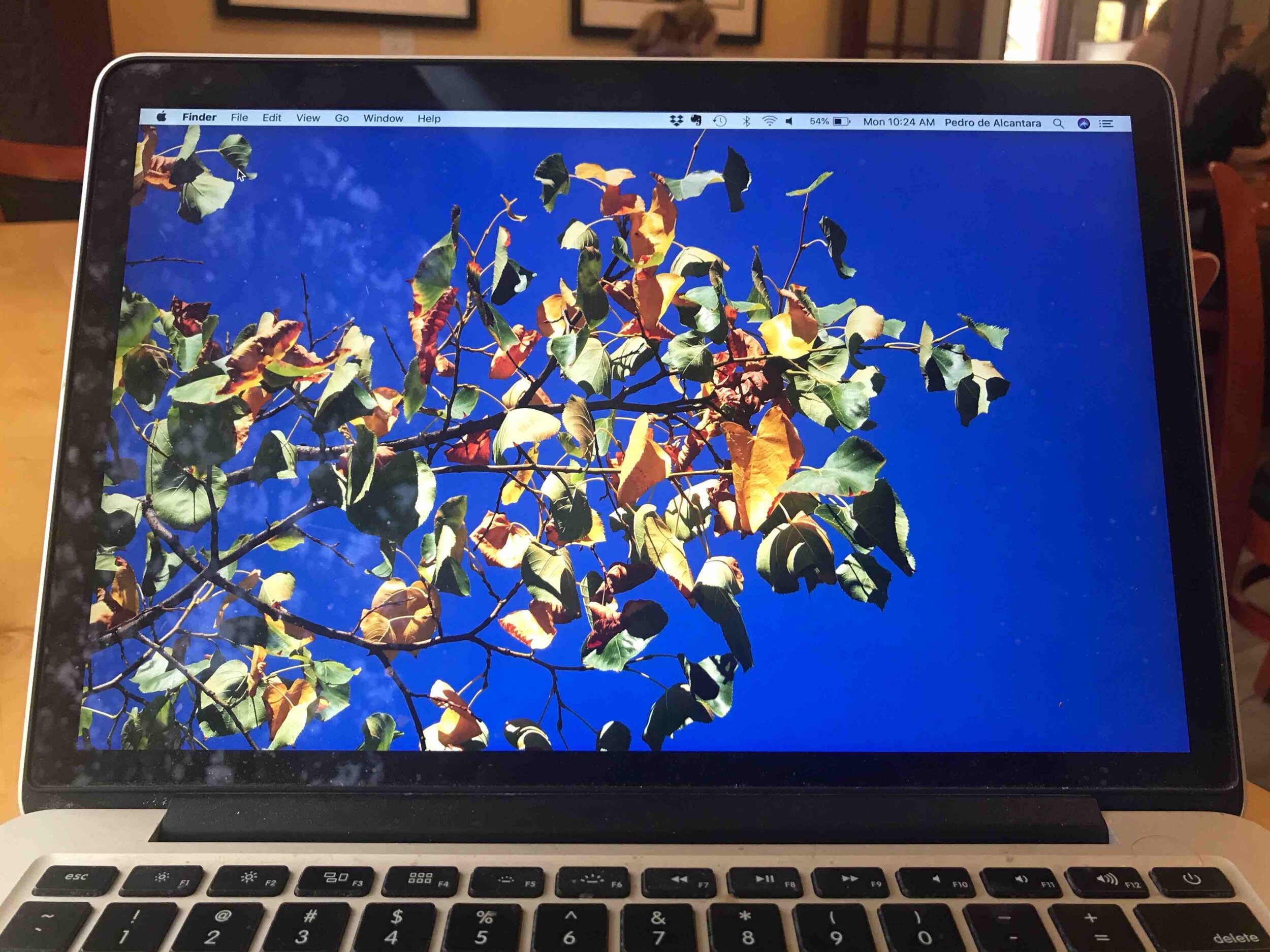

I’ve been going through my computer files and deleting old stuff I don’t need anymore. A Word-file business letter from 2002, for instance, recording a transaction that I barely remember and that has no bearing on my life now. Files generated by obsolete software. Duplicate or near-duplicate images: three or four or seven snapshots of a tree, the snapshots only a tiny little different one from the other.

I have thousands and thousands of such files piled up willy-nilly and helter-skelter and boogie-woogie in my computer.

Junk? Did you say junk? Did you call my files junk? You’re right. Thanks.

With digital files as with life, we need to make constant decisions about what to chuck, what to keep. This applies to material things (objects, clothes, books) and immaterial entities (words, thoughts, habits). Writing this post, for instance, I had to make dozens and dozens of choices regarding words and images. I kept what you’re now seeing, I chucked a whole bunch of stuff.

Socks with holes: chuck or keep? A famous book from the literary canon that you bought in college thirty years ago and that sits in your bookshelf untouched and unread: chuck or keep? A fingering that you tested for a melody you play at the cello: chuck or keep?

The principle of chucking or keeping manifests itself through you a thousand times a day. It’s useful to notice how often you have to do it, and it’s useful to decide to become better at it. The Japanese have a word for the concept:

チャッカーキーパー (pronounced chakkākīpā)

I don’t enjoy shopping for clothes. If I find a shirt that I like, I buy two of the same, sometimes three of the same. On occasion I’ve regretted not buying four of the same. One of my shirts is “me.” I get compliments on the way its color (I’d call it “beryl”) enhances my eyes. Someone told me the shirt is the color of dopamine (I think it was a compliment). I have two of these shirts, and I wish I had an endless supply of them. The ones I have are beginning to fray.

But four very similar snapshots of the same pizza slice? A single shot is enough for most purposes. It’s possible that zero snapshots of the pizza slice would be even better. The moral of the story: take fewer pictures, and keep fewer of the pictures you take. Besides pictures, this applies to all objects and things. If possible, zero; if not possible, one; if it’s a nice shirt, four.

In the chakkākīpā method, this is called zero-one-four, or ゼロワンフォー(pronounced zerowanfō).

Big collections of fiddly bits can be absolutely fascinating. Let’s take the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford as an example. It’s a sort of anthropological and archeological warehouse, where a huge number of objects from all over the world are displayed in crowded cabinets. It gives you an incredible overview of humanity and its history and its psychology.

The museum is spectacular, and . . . it’s ethno-hoarding gone bonkers. Flinty this, toothy that, hair this, bone that, knife this, spoon that, twenty-four of the same. Let’s imagine a two-room art gallery one-hundredth of the size of the Pitts River, with a small selection of meaningful and beautiful objects soberly displayed. The gallery might be called “The Gist of it.”

What is an exoskeleton? It’s a skeleton worn on the outside of the body: cockroaches and lobsters. What is an exo-mess? It’s a mess that you delegate to an environment other than your home; a mess you can visit, rather than a mess you have to live with. The Pitt Rivers Museum is marvelous, and I’m happy it exists, and I’m happy it’s there and not here. Symbolically, move the Pitts out of your life, and live in “The Gist of It” instead.

In chakkākīpā, this is called exo-, エキソ (pronounced ekiso).

Suppose your computer desktop is full of files vying for attention. Create a folder and put ALL those files in them. Now your desktop has nothing. It means you can choose between looking at a clean, clear, soothing image (“The Gist of It”) without files and tasks and duties and tortures; or looking at a big collection of files (“Pitt Rivers”) which are of course useful and vital, easily accessed, and not poking you in the eye every time you open the computer.

Chucking things doesn’t mean eliminating the mess altogether; it means “playing with it.” Mess is good, mess is necessary, mess is inevitable. There’s a place and a time for it, literally and symbolically. Mess is an aunt who lives in the outskirts of town. The aunt is called Imelda Hazardous Materials Unroadworthy Rodent Smith. She’s terribly amusing and you visit her willingly, but—hey, it’s soooooo wonderful that you get to go home afterward.

In chakkākīpā, this is called Hazardous Materials Unroadworthy Rodent, 危険物のロードできないネズミ (pronounced Kiken-mono no rōdo dekinai nezumi, short form rōdo).

Now you know.

©2019, Pedro de Alcantara

from my favorite website, https://www.etymonline.com/