The Buddha and the Shadow met in a bar. One of them was resplendent, the other stank of sulfur. Jack, the bartender, knew them well. “The usual?” he asked.

“Yes,” they answered in unison. A Bloody Mary for the hairy one. And a shot of nothing, with a prāna chase, for the other fellow. Plenty of peanuts. The Buddha had a thing for crunchy-salty-nutty.

“What’s that smile about?” the Shadow asked.

“Unconditional love,” the Buddha answered. “I feel good.”

“Oh yeah? Have a look at yourself in that mirror behind the bar. You’re as fat as a Buddha, and you’re 2500 years old.”

The Buddha chuckled. “You’re right, I should lose some weight. But these peanuts . . .”

“It’s not the peanuts, Fatso. That smile of yours is just phony.”

The Buddha chucked again. It’s what he did—smile, chuckle, laugh, smile, chuckle, laugh. It drove the Shadow insane.

“Dimples are for little kids,” the Shadow said. “On you they look like leprosy.”

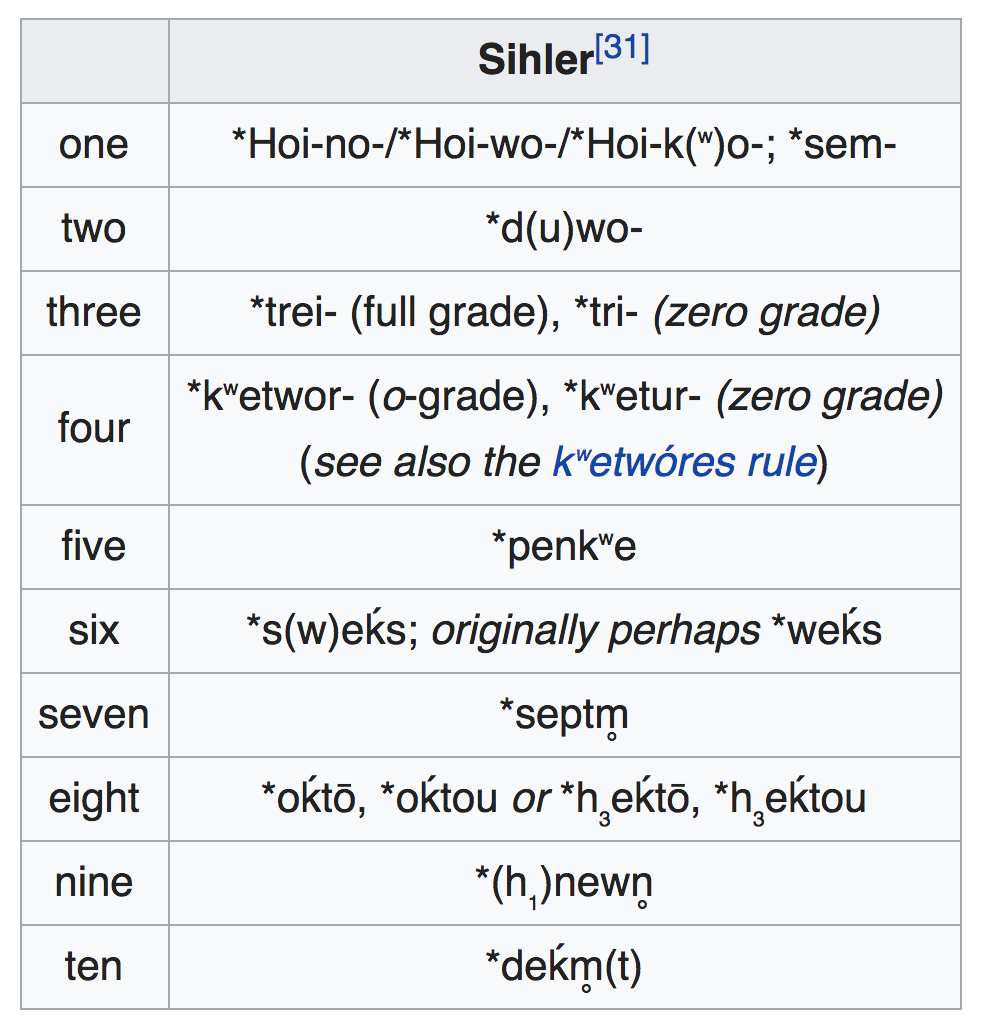

“Marvelous,” the Buddha chanted, beaming. “Did you know that the word ‘leprosy’ comes from the Proto-Indo-European root ‘lep’? Back then it meant ‘to peel.’”

The Shadow finished his Bloody Mary in one gulp. He banged his glass on the counter, and Jack heard it loud and clear. “You and your stupid Proto roots,” the Shadow said. “I have a PhD in linguistics. I happen to know that ‘lep’ also evolved towards the Lithuanian ‘lepus,’ which means ‘soft, weak, effeminate.’ Google it if you don’t believe me.”

“Here it is, buddy.” Jack served the Shadow his second Bloody Mary. It wasn’t going to be his last.

The Buddha smiled again. “Jack, let me have another shot of nothing.”

“Nothing!” the Shadow shouted. “That’s what’s wrong with you! You believe in nothing, you feel nothing, you do nothing! You’re dead inside!”

The Lord Buddha laughed silently, and his rolls of fat wiggled and jiggled. “Shady, I love you just so.”

The Shadow couldn’t take it any longer. “You—you—you—” He lunged at the Buddha and grabbed his throat, having temporarily forgotten that Fatso had learned karate when he dwelled in Japan.

The Buddha shoved a knee into the Shadow’s groin. He collapsed on the floor, writhing in pain. Fatso stomped on his head and—well, he killed the guy.

The bar fell into a deep silence. In the distance, the church bells sounded midnight.

Jack knew the drill. He put another Bloody Mary on the counter, plus a big bowl of peanuts. In walked the resplendent Lord Buddha, smelling of sandalwood and patchouli. “Shady!” he said. “You started drinking without me. What’s bothering you?”

“Don’t even ask,” the Shadow replied, sipping his Bloody Mary. “Tonight I could murder somebody.”

©2019, Pedro de Alcantara