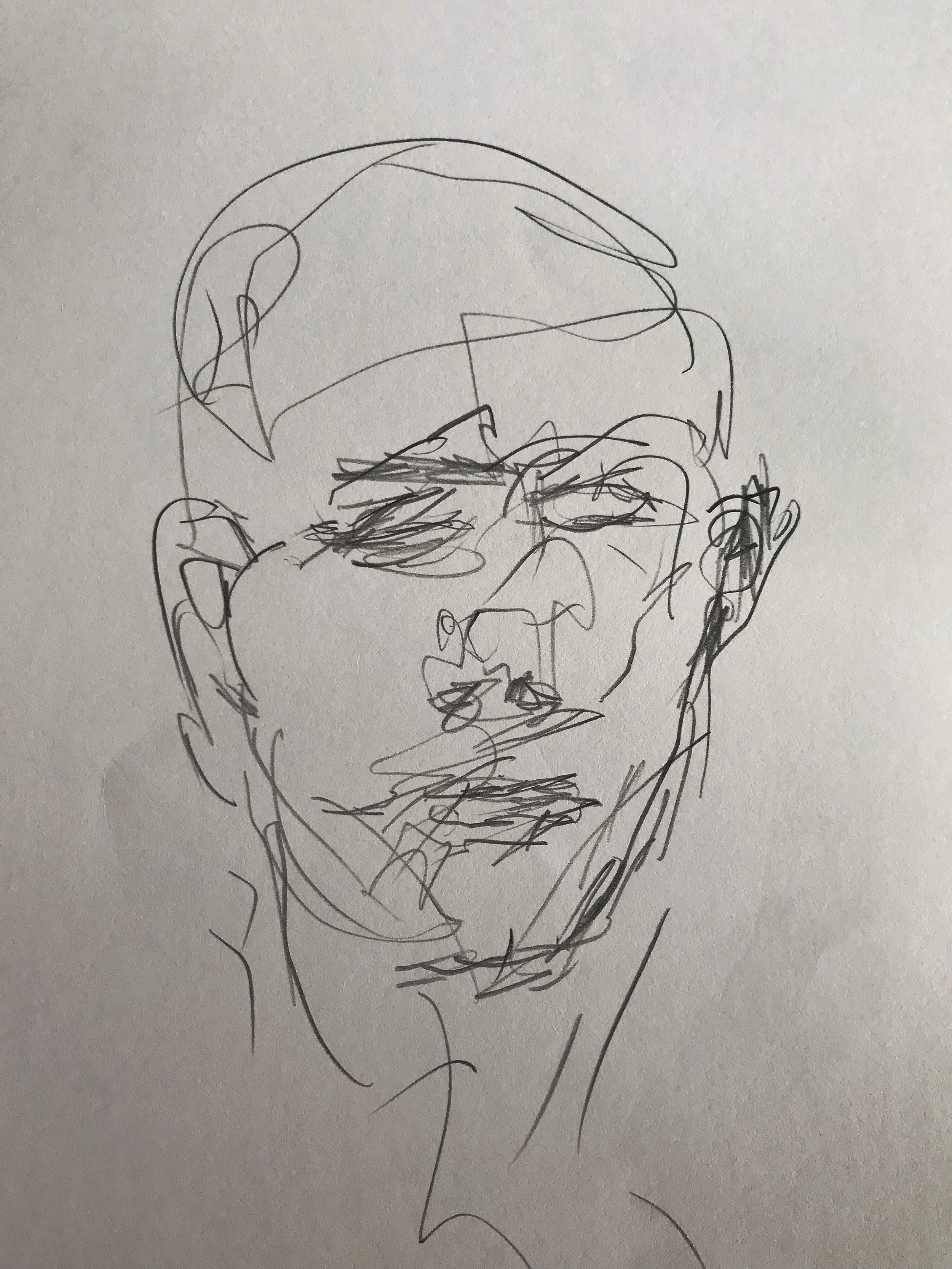

All day you shrink and you expand. It’s a natural process that you can’t avoid. You might as well embrace it.

You get out of the shopping mall only to find out that somebody has parked too close to you. You can only enter your car by making yourself smaller than your habitual self. You might be annoyed and unwilling, but you’re going to become a boneless marshmallow anyway, because either you shrink-to-enter-and-drive-away or you don’t go anywhere.

A mosquito is resting on the wall behind your bed, all the way up near the ceiling. The mosquito has just drunk a quart of your precious blood, and you’re going to expand in body and in mind, and with a paperback book from your nightstand (Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair) you’ll stretch heavenward and take revenge. If you could see a movie of yourself reaching for the mosquito, you’d be amazed at how big you suddenly look, how long, how strong.

Can you pass through a tight space when you’re that big, that long, that strong? Try it, and if you survive the experience send us a report.

It's not just mosquitos and drivers that make you shrink and expand. Ride the subway at rush hour and you’ll make yourself an “invisible gray cabbage,” to coin an expression. People will be pushing into you front and back, left and right. To avoid even the impression of intimacy, you’ll dial down your energy field, “as if you were a vegetable.” You don’t have to be a cabbage; rutabaga works well, too. The word “rutabaga” comes from the Swedish for “lump.”

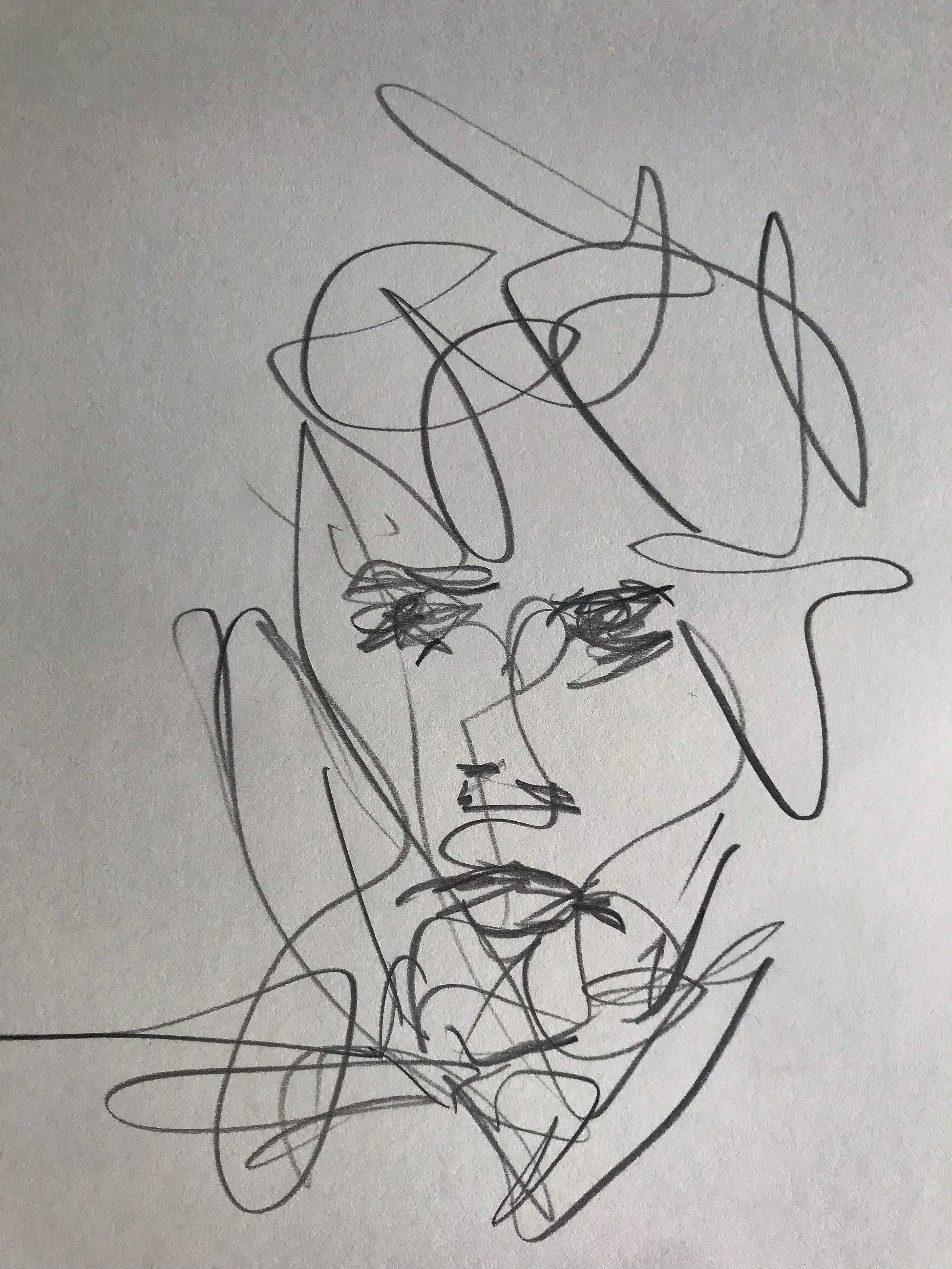

You’re at a vernissage when you catch sight of your ex, who’s suing you for alimony, mental-distress damages, and custody of the remaining parakeet. You “disappear,” even if you stay in the gallery. Or you’re at a vernissage when you see an art dealer you’d like to impress. You “appear.” It’s absolutely essential for you, and for all of us, to know how to appear and to disappear according to the needs of the situation.

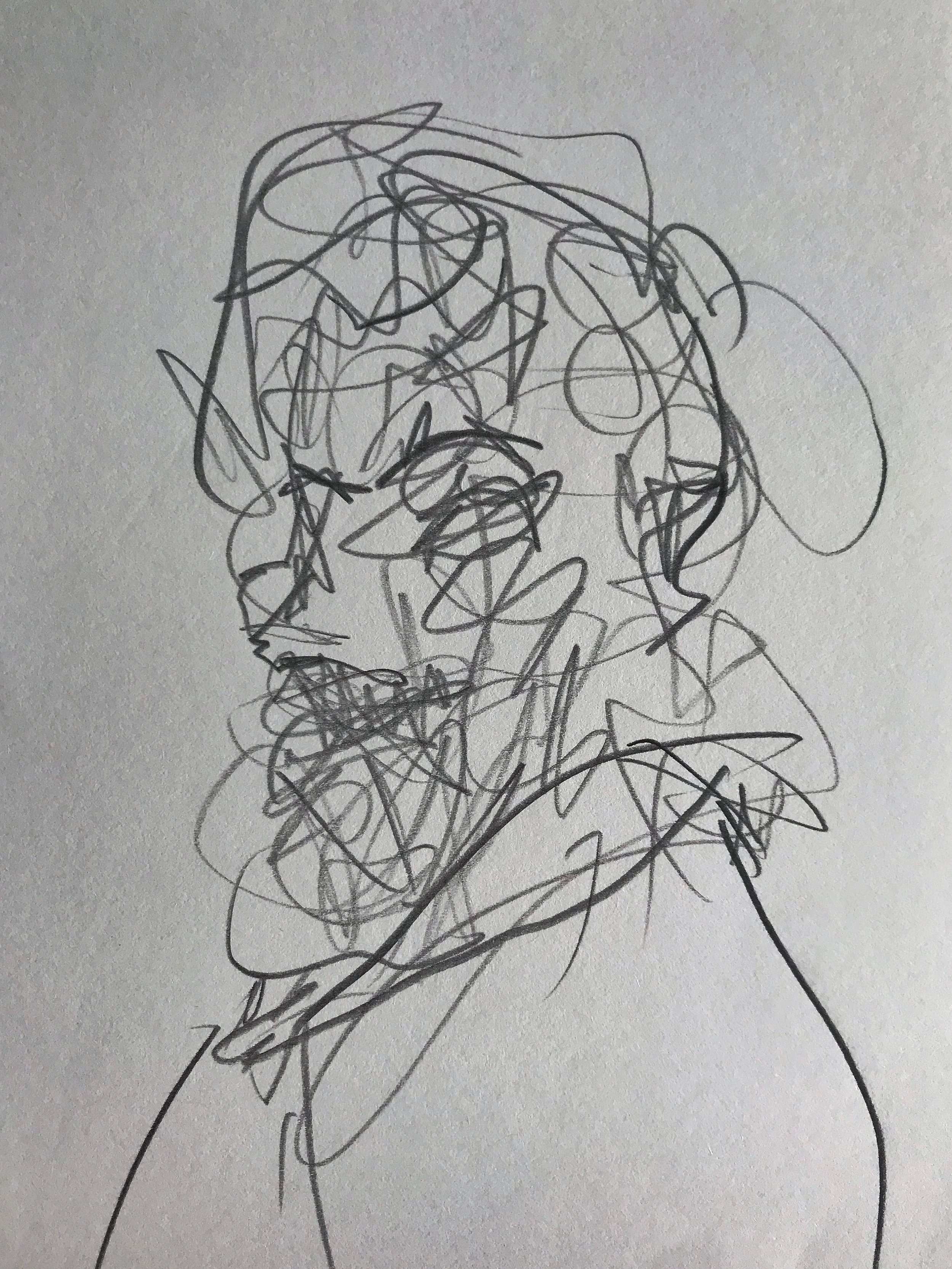

Thoughts alone can make you shrink or expand. Memories of a dental procedure make you shrink. Memories of a beach holiday make you expand. The same stimulus can make some people expand and others, shrink. I know lots of people who automatically shrink if you give them a compliment. To them, “expanding under compliment” would be wrong, inappropriate, and immoral. It might be useful for them to work through this issue and become better able not to shrink automatically.

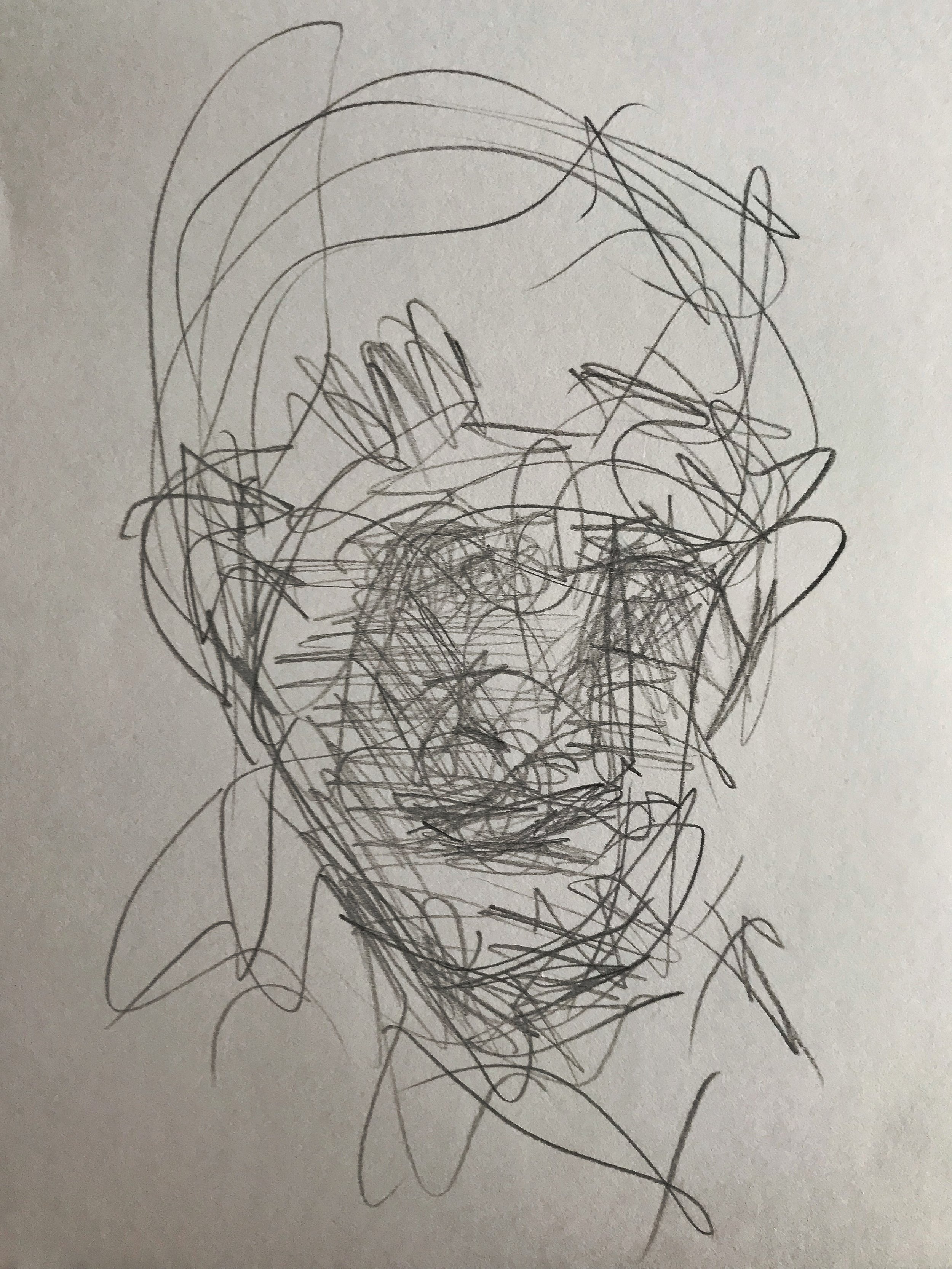

Control your shrinking and expanding self, and you control your life. Let’s make some extravagant claims without evidence from neuroscience: Many illnesses arise from a dysfunction of your inner shrinking-expanding mechanism (“accordion”). People die of psychic shrinkage, of not reaching out, of not fulfilling their destinies, of not occupying the space they need in order to breathe, move, learn, and grow.

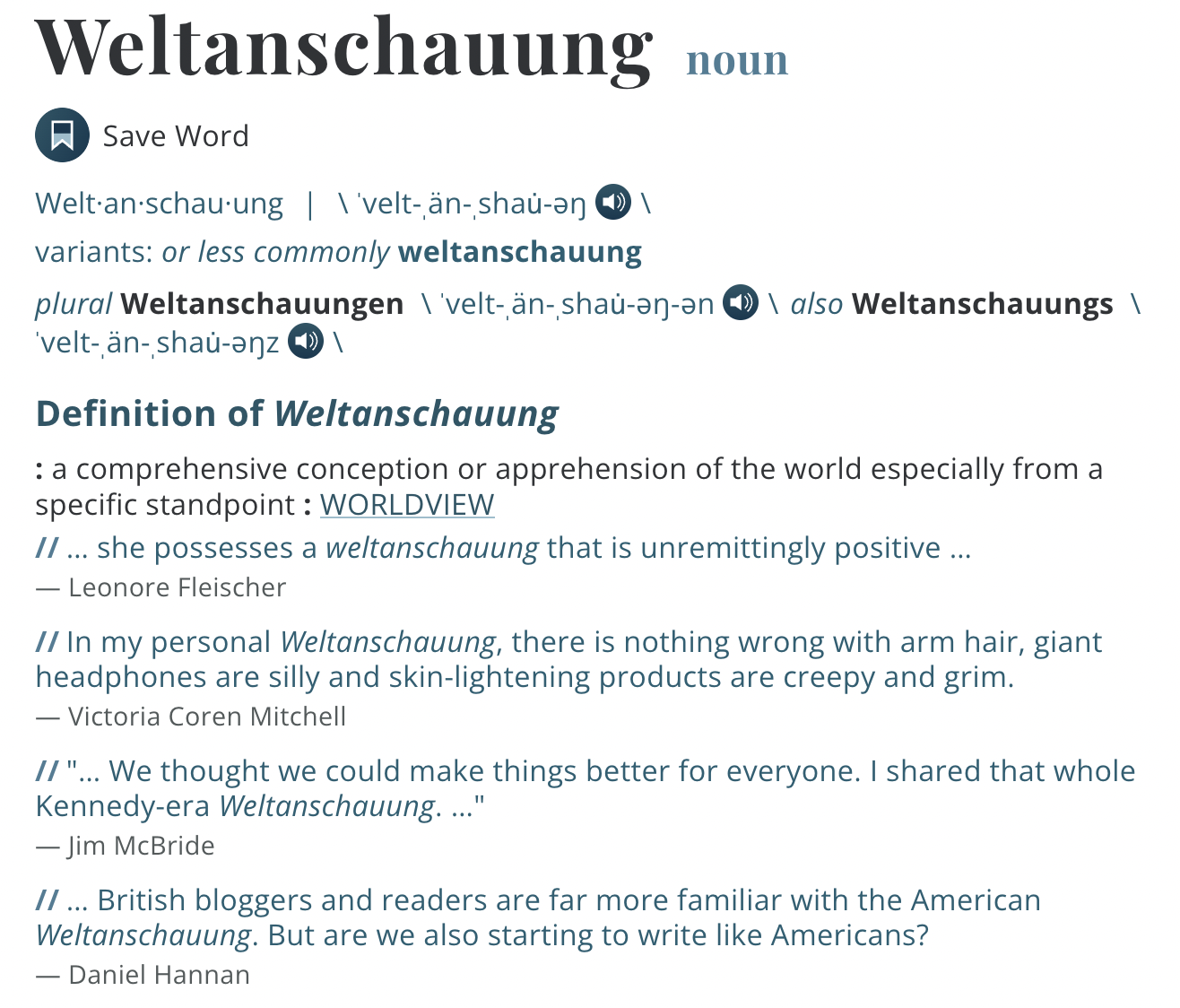

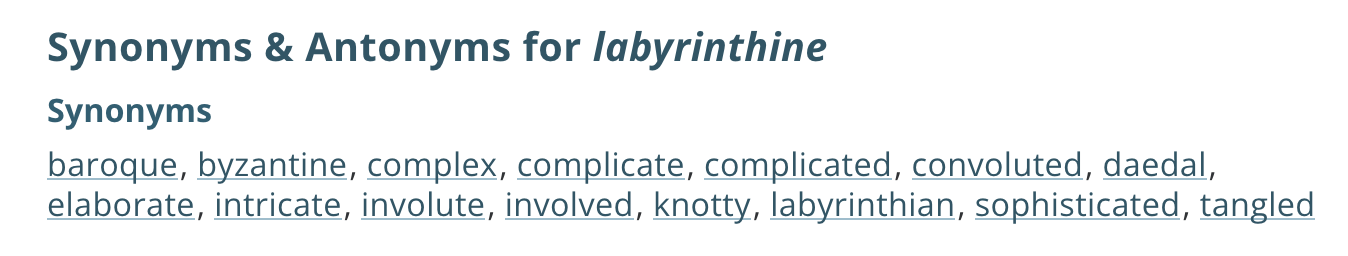

From my favorite website, www.etymonline.com

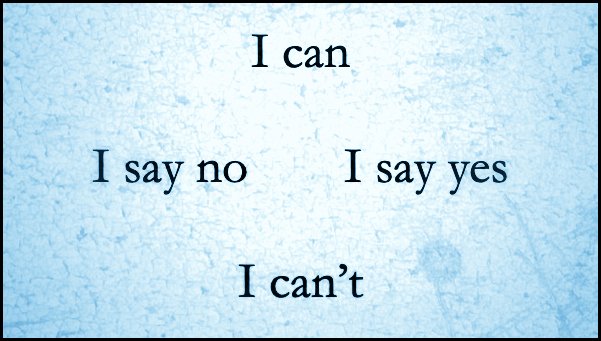

People also die of misdirected psychic expansion, of ego inflation, of hubris (which is Greek for “run riot”). Career success is accordion virtuosity, matching your talents to the twisting paths that take you forward. Existential equilibrium comes from comfort with the cycle of inflation and deflation, both of which are necessary. It’s their interplay that “makes music,” and it’s their music that “makes you dance.” Commitment and distance, in and out, up and down, yes and no, now and later; ocean tides, the workings of lungs and heart, bursts of activity and rest, effort and depletion, decay and rebirth are all manifestations of the Accordion Principle.

Here's a famous Jewish proverb: “Too modest is half proud.” You don’t do yourself or anyone else any favors by calling attention to how good you are at shrinking, so good but oh-so-good that you deserve a medal. If you’re a mensch, shrink authentically.

And here’s a famous proverb from my native Brazil: “Mosquito inflate, mosquito deflate.” That’s a rough translation, of course; back home we say “Sucker bloater splatter croaker, hasta la vista capitalista.”

From my favorite website, www.etymonline.com