Every process is a learning, and every learning is a healing. I know, I know; this is too absolute a statement, starting as it does with “every.” Every statement that starts with “every” is too absolute, therefore not true.

We start again: Some creative processes involve a lot of learning, and through the learning you get to feel good about yourself and about other people.

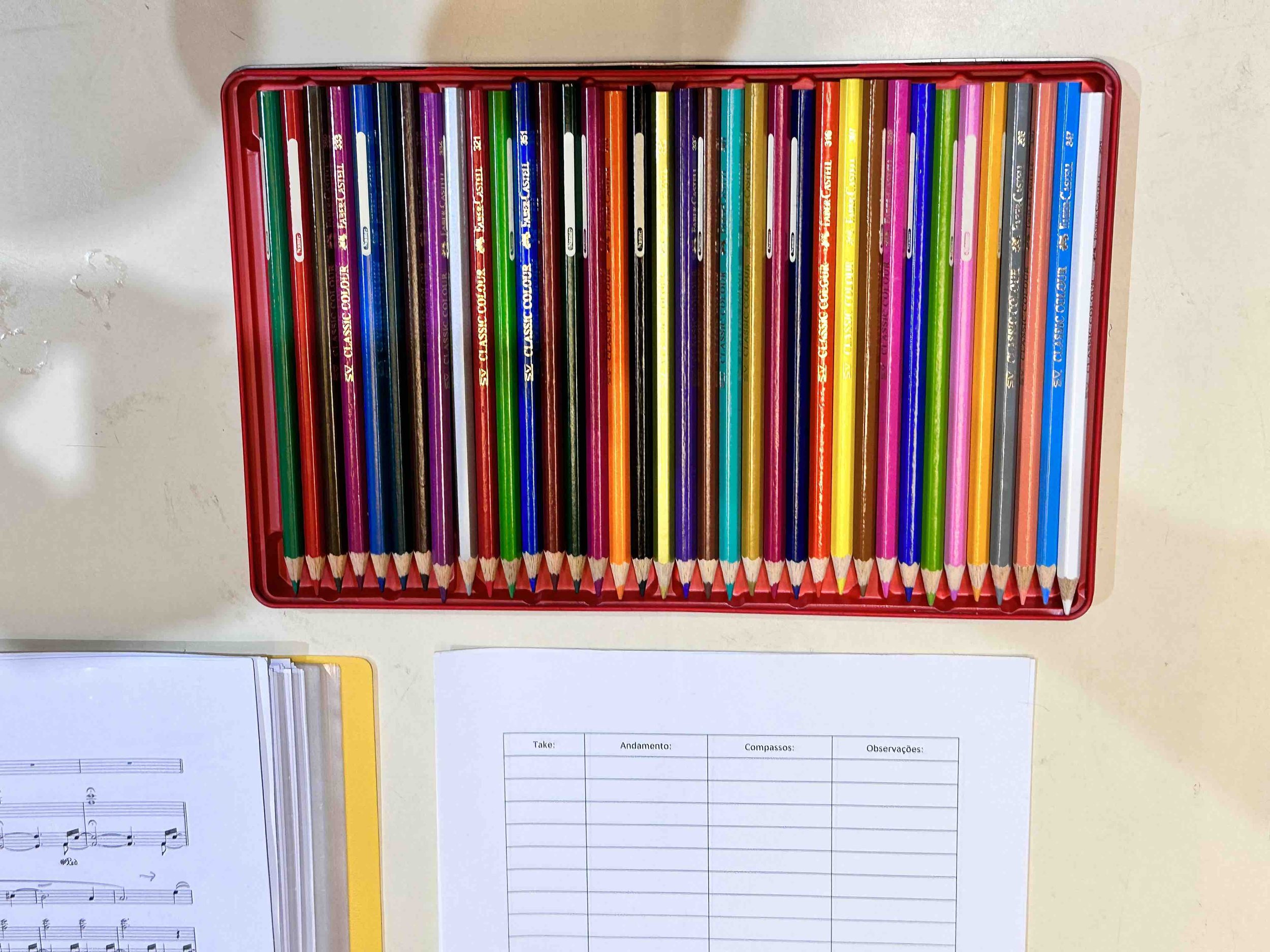

I recently spent a day recording four tracks of contemporary music for a CD project led by my friend Katharine Rawdon. An American flutist, composer, and improviser, Katharine has lived long enough in Lisbon to have become a Portuguese citizen. We recorded in Coimbra, a monumental city in the Portuguese heartland and the home of a great university first established in 1290. Yep, just short of a thousand years ago.

From any one fact we can draw connections to any other fact, usually through a hyperlinking sequence that only takes a handful of steps.

Coimbra >> university >> tradition and innovation.

An American in Lisbon >> A Night in Tunisia >> Casablanca.

Katharine >> Catherine of Aragon >> Sergio Aragonés >> MAD Magazine.

The creative process thrives on hyperlinking, even though hyperlinking gone wrong isn’t that different from paranoid psychosis, schizophrenia, and playing the cello upside down. It’s useful to know when and how to hyperlink, and when and how to wear a lead helmet to protect your brain from hyperlinking.

Lead helmet >> Helmut Kohl >> Kohlka Kola >> “Oh Calcutta!”

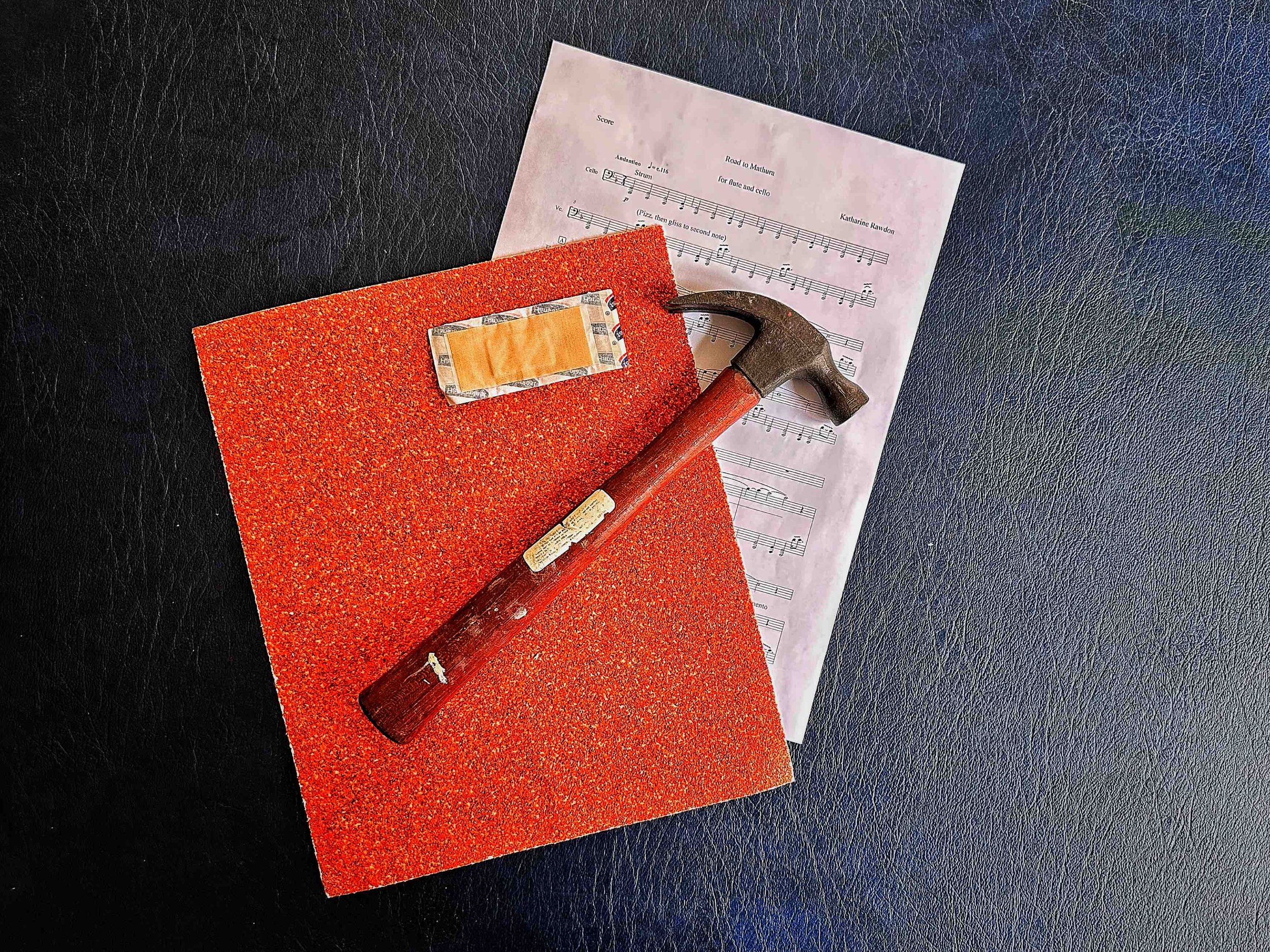

Katharine’s CD project contains about 12 pieces; my contribution to the program is partial. We recorded a piece of mine that I wrote ten years ago. Originally for voice and piano, on this CD “Disconsonance” will live in a gorgeous version for bass flute and piano, with me playing the piano. Katharine also wrote a bass-flute and piano piece, just as gorgeous: “Cerulean Voyage.” We also recorded Cindy McTee’s “Stepping Out,” for flute and claves (with me as the newborn clavista). Most importantly, we grappled with “Road to Mathura,” a piece that Katharine wrote for the two of us in which I have to sing, play the cello, and play percussion simultaneously, in 7/4 time, with polyrhythms and pizzicato and col legno and sul tasto and three-against-four and everyone-against-me. Blisters and calluses, fingers and brains, ketchup and mustard.

In advance of the recording, Katharine flew to Paris a few times for us to practice and rehearse. Together we tweaked the various compositions, helped each other learn our parts, talked, laughed, had dinner, laughed. The thing is, I couldn’t play any of those compositions perfectly, and I couldn’t play the blisters-and-calluses festival with any semblance of precision, comfort, mastery, inspiration, delicacy, intelligence, or sang-froid.

Sang-froid >> reptile >> swamp >> methane >> stink.

But, hey, we rehearsed, I practiced, I practiced some more, I got the hang of a couple of sections in the complicated piece, I practiced lots more and evermore, and by the time of the recording I didn’t embarrass my late mother, may she rest in peace wearing earplugs.

There was a week’s period immediately before the recording during which I didn’t play the cello, and I didn’t even have my cello with me. I recorded on Katharine’s daughter’s cello, and I only got the borrowed cello the day before the recording. Beforehand I gave a workshop in Porto, then I spent a few days in Matosinhos, a beach town right next to Porto. I worried a bit about the blisters and calluses that I had built up in Paris. A well-placed callus somewhere in your left thumb really helps you pluck those thick cello strings. A week without practicing, and your fingertips become as tender as the rear end of a baboon.

Baboon >> buffoon.

I went to a hardware store in Matosinhos, a couple of blocks from the AirBnb I had rented with my wife Alexis. Two ladies worked there, mother and adult daughter. I explained my predicament to the daughter.

“I’m a cellist, I’m preparing to record a CD in which I have to pluck the strings, and I need to build up some calluses. Do you have some bit of wire or something that resembles a string that I can pluck until I have a blister, and until the blister becomes a callus?”

“Let me think.” She went looking here and there, and she came back with a potato peeler. “Maybe you can caress the blade.” Sure, sure.

My wife was with me. She too had an idea. “How about sandpaper? You could rub sandpaper and build some resistance.”

I bought the peeler and a sheet of thick sandpaper. At the checkout, mother and daughter started expressing themselves. The daughter said, “Potatoes and carrots,” and air-peeled some. The mother said, “I only do potatoes. I’m left-handed.” I was certain that, as a child in conservative Portugal, she had been forced to write with her right hand, the left tied behind her back. I asked her about it, and she confirmed it. “I write with the right hand, but I can also write with the left.” I asked her to show me, by writing “Pedro de Alcantara” down on her notepad, with the right and the left hands in turn. She got into it. Both versions were legible. I asked her, “When you’re mad with your daughter, do you slap her with the right or with the left hand?” “The left, of course,” she said, laughing.

At home I rubbed my left thumb on the sandpaper. Soon it became red and raw, like a wound. My worry about the recording went up a notch. “Maybe the wound will be better by the time of the recording,” my wife said, her voice melding hope and apprehension.

Baboon >> good afternoon >> go home soon.

The hardware store, the mother and daughter, my wife’s devotion, my workshop in Porto, the daily round of beach walks and city explorations in Matosinhos, the fresh foods; Katharine Rawdon’s talent and friendship, our shared love of music, our Paris rehearsals, our laughing together: the recording went extremely well.

The process is a learning, and the learning is a healing. Uncertainty and risk-taking, preparation and humor, pacing and rhythm, trust and faith, sandpaper and potato peeler. Take the lead helmet off and you’ll solve all your problems.

©2023, Pedro de Alcantara