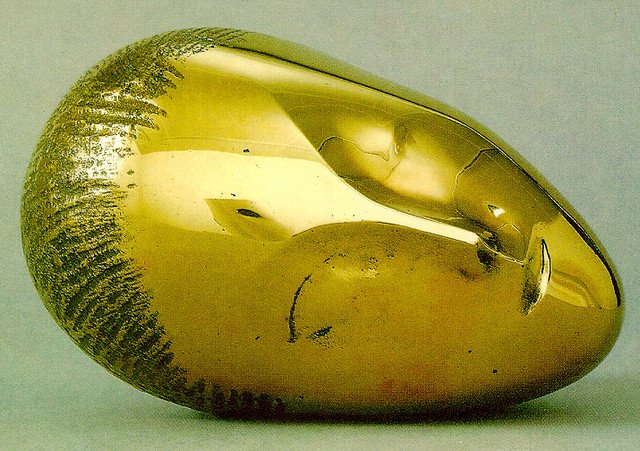

Let me paraphrase Constantin Brancusi (1876 – 1957), the great Romanian-French sculptor: “Things aren’t difficult to do. What’s difficult is to put ourselves in the state of mind of doing them.”

What exactly did Brancusi say, when, and in what language? What did he mean by it, and how did he embody it in his life and work? “I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know, and I don’t know. But here I am, feeling good and sensing that his words–or these words attributed to him–might be useful to me and to some of my readers.”

Principle #1: Acknowledge the subjectivity of interpretation. Principle #2: Acknowledge the limits of your knowledge and understanding. Principle #3: Feeling good is generally more helpful than feeling bad.

To make an omelet, you need to break some eggs. And you need some eggs to begin with. A chicken needs to have laid some eggs. And the supply chain needs to bring some eggs to within your reach. And the logistics experts—never mind. You get my point.

Principle #4: There’s always a thing before another thing. Your state of mind precedes and prepares your actions. It actually determines your actions.

The notion of difficulty varies from person to person. For someone, giving a speech in public is a breeze, a delight. Anytime, sure! Any subject, sure! And for someone else, it’s torture. Many people actually say they’d rather die than speak in public. And the gentleman or the lady who loves speaking in public hates opening cans of tuna. They’d rather die of hunger, or order in, or eat reheated chulé de ontem (where I come from, this isn’t a delicacy). Anything but the can!

Principle #5: To be human is to face difficulties. And to be this one human is to face difficulties potentially quite different from those other humans.

Suppose you know for a fact that you will definitely do something that you’re dreading but that you can’t avoid. Typical examples are dealing with in-laws, dentists, tax officials, or funeral arrangements for people other than your mother-in-law. But humans are quite different one from the other, and there are people who love their mothers-in-law (to death!). These are just illustrative examples. I start again: You’re definitely going to do something that you’re dreading. Then it really helps if you actually agree to do it. It’s going to happen anyway, right? You might as well diminish your resistance, resign yourself to the activity, and do it.

Principle #6: Kicking and screaming, you end up hurt yourself first and foremost.

How long does it take to learn a foreign language? As long as it takes. How long does it take to go through your tax receipts? As long as it takes. How long does it take to embalm your mother-in-law? Actually, this is the exception to the rule, thanks to the advantages of incineration.

Principle #7: Agreeing to take the time needed to accomplish a task shortens the time needed to accomplish it.

What are you actually trying to accomplish or make or get rid of? Some clarity helps. You don’t want to incinerate the wrong person just because “you weren’t thinking.” This applies to all tasks, however simple.

Principle #8: Clarify the task, and clarify the intermediate steps needed to accomplish the task. Don’t take your own clarity for granted. Incineration is irreversible.

Brancusi was a great artist who made the most beautiful sculptures and who had an interesting, meaningful, rich life. He entered immortality through his creative efforts, his discipline, his risk-taking. By most measures, or perhaps by all measures, he’s a much greater artist than myself, for example. I don’t stand a chance!

Principle #9: Comparing yourself to other people distracts you from that frame of mind in which it’s easier to do things.

Brancusi also said this:

Simplicity is complexity resolved.

Create like a god, command like a king, work like a slave.

To see far is one thing, going there is another.

Whoever does not detach himself from the ego never attains the Absolute and never deciphers life.

Principle #10: When it comes to the frame-of-mind thing, wonderment and gratitude tend to work better than envy and jealousy.

©2023, Pedro de Alcantara