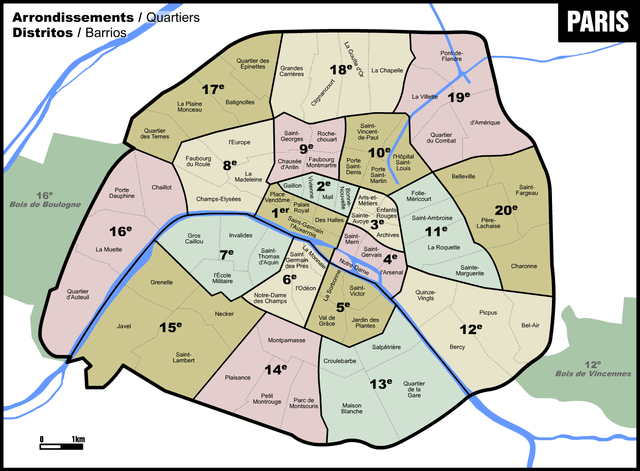

Paris isn’t a city, but a universe. The city is divided into 20 arrondissements, traditionally organized and numbered as a sort of spiral or escargot. Every arrondissement is divided into four quarters, which the French of course call quartiers. Twenty arrondissements, four quartiers per arrondissement, 80 named neighborhoods. It’s not too much of a stretch to see Paris as 80 villages glued together. And each village is full of history and architecture, hidden corners and courtyards, secrets and mysteries, wonders and miracles.

Paris the universe is multilayered. Food and wine? Yes, explore this dimension as a full-time job, and you’ll never exhaust all its possibilities. Architecture? Thousands of buildings in every style, and new interesting buildings coming up every year. Fashion; urban planning; public transportation; cinema; theater: the word “thousands” apply to every dimension, as in thousands of details, thousands of possibilities, thousands of discoveries.

But this post isn’t about Paris per se, but about Émile Salimov. We’ll get to him soon enough, but first let’s mention that art is one of those incredible dimensions of the incredible universe of the incredible 80 villages. Two dozen world-class museums; another four dozen lesser museums of great charm; dozens and dozens of art galleries; dozens and dozens and dozens of ateliers where dozens and dozens and dozens and dozens of artists of every stripe spend their days in creative exploration.

One of the villages in Paris is called Belleville, out in the 20th arrondissement northeast of the city center. Immigrants from all over the world living in a swirl of action and color, of languages and sounds, of hopes and fears.

Belleville organizes a yearly open-house weekend, during which you can visit the ateliers of some of its working artists. This year there were 156 participating ateliers. You get a map, and you walk here and there, you enter courtyards, you find secret doors, you enter, and you see. And you chat with the artists, many of whom have much to say.

It's overwhelming.

My wife Alexis and I went out there on a sunny Saturday afternoon, walking all the way from our home near the Bastille and the Place des Vosges. (Technically our own village is called La Roquette.) To choose from a menu of 156 possibilities, give up any pretension of discernment and just go somewhere, then somewhere else, then somewhere else.

We had a good and a great time. Every second courtyard was gorgeous; every second city block was fascinating; every second shop window was a festival of visual and olfactory stimulation. Some of the artists’ ateliers were wonderful spaces that made us salivate, real-estate-wise.

And some of the art was touching, interesting, clever, stimulating. Or annoying and distracting. Or oy-vey-ay-caramba-oh-la-la-mein-Gott-get-me-out-of-here.

Art is art. It’s not possible to say brief, original, and meaningful things about what art is or what art should be (and I’m using the word “should” as a joke). Instead, let me say something general and vague, coming from the village of Useless. Art can be a quest for expression or a quest for connection. The quest for connection is, in itself, a form of expression. But not every quest for expression leads to connection. Expression might be summarized like this: “I made this. Look at me.” Connection is more difficult to explain, but it arises from the timeless and mysterious, the ambiguous and paradoxical: “I made this, and this made me. You don’t need to look at me at all; instead, look at this.” Now a connection is established—with the creative source, with eternal myths, fables and stories; with nature and the workings of Space-and-Time; with archetypes, with structures, with inklings; with ineffable principles that we can’t describe or even name.

Our randomized meanderings through Belleville led us to a modest apartment in a modest corner on the edge of anonymity. Entering it, we immediately knew that we had passed from the world of expression to the world of connection; from the world of I-made-this to the world of this-made-me. It was magical.

Meet Émile Salimov. Look him up on Wikipedia, and you’ll see that he’s a theater man from a faraway place called Azerbaijan-Russia-USSR-France-Here. The place has specific cultural and linguistic characteristics, and yet it could also be called Nowhere Somewhere Everywhere: its language is Story; its culture is Love; we all live in it, although some of us aren’t alert to our shared nationality.

Émile Salimov is alert to it, and also to It. (Uppercase changes mere physics to Metaphysics.) If you look at his art you’ll also become alert to it, and to It. His art will remind you of things you’ve always known but have forgotten or neglected; his art will turn you into a child, and an enlightened adult, and a child; his art will make you want to read, listen to music, sing, learn languages, travel, go for nature walks, have strange dreams at night, open up, absorb, integrate, and Become a Citizen of the Country called Story.

This is perhaps only a detail, but Salimov’s art happens to be very skillfully created. High-grade markers that penetrate and transform paper; thought and care; patience and discipline; form and color, form and color, form and color.

After we saw Salimov’s collection we walked straight home. It didn’t seem right to seek other urban or artistic experiences. The day after, I felt compelled to return to his show and to spend more time looking at his work and talking to him. There were 155 other artists clamoring for my attention, but the quest for connection had taken me where I needed to be.

©2024, Pedro de Alcantara